The older of the two old men next door dumped a can of beans on the lawn. It was just one of many dishes fed to four or five cats that hung around their house and lounged the day away sunning on their fuchsia wooden porch or yellow stone walkway. The men who lived there were strange. One was in his fifties, the son, the other in his seventies, the father. Both were widowed, both clothed eternally in plain white T-shirts that hugged their immense guts.

We spent our nights listening to their TV set blare and watching white lights flicker between their blinds with the changing scenes. Their TV never stopped.

They were recluses. But the son could be seen leaving every now and then with a pool cue case, and sometimes he flushed the radiator of his car in the driveway. The father only ventured out to buy 12-packs of sodas. On cool nights they might come out—one at a time—on the porch to pet the cats. I would watch the red glow of their cigars wax and wane in the dark. Neither man spoke much, but always in kindness when they did. It worried me. I wondered how many dead were buried in their back yard. But they only dumped beans there, and sometimes partial loaves of white bread, for the cats. Sometimes we awoke to a screeching scuffle over the food.

As time passed, the father began to talk to us more and more, in pleasantries. “How are you? How was your trip? Sure was a bad storm.” Eventually, we always made it a point to address him. The son, however, was only spoken to if his eyes met ours—a rarity.

When we told the father we were leaving Austin, he inquired where. We told him of our new house perched off the highway near Privilege Creek, south of Bandera in the Hill Country. “Ahh,” he said. “My wife is buried there.” I figured he was mistaken, confused, for I never saw any cemeteries there. “He must mean Pipe Creek,” I thought. Before we left Austin we asked another neighbor for the names of the strange father and son, since we had never asked ourselves in the two years as neighbors. “Mr. Obiedo,” she said.

Four months later, on a clammy summer morning, I decided to ride my bike down Privilege Creek Road, a twisting course that headed east from our house on Highway 16 into the hills. I scared deer in the brush. I crossed creek bridges and splattered water up my back. I spied a black billy goat with his flock and almost called out to him. I outran a territorial pit bull. I saw a sign that said, “Polly’s Chapel.” I followed the sign along a dirt road by the creek. Rusted farm equipment waited in the fields. My anticipation pushed my legs further, up a final rocky hill to a small stone church pointed with a steeple. No songbirds. No crickets. No wind in the trees. Only my heaving breath.

And the chapel’s cornerstone read: “Iglesia Metodista Episcopal Del Sur. Abril 17, De 1882.” Polly’s Chapel, according to its historical marker, was built by hand, by Jose Policarpo Rodriguez, a scout turned preacher. Before I continued on, I wanted to leave a sound, so I pulled a rope by the chapel door and rang a bell in the belfry, softly.

And the chapel’s cornerstone read: “Iglesia Metodista Episcopal Del Sur. Abril 17, De 1882.” Polly’s Chapel, according to its historical marker, was built by hand, by Jose Policarpo Rodriguez, a scout turned preacher. Before I continued on, I wanted to leave a sound, so I pulled a rope by the chapel door and rang a bell in the belfry, softly.

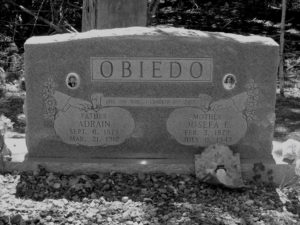

To the left of the chapel, a hundred yards or so down the road, was Polly’s Cemetery. The plots were fenced in with barbed wire, and nearly a hundred cow patties pockmarked the ground in front of a large, iron entry gate. Inside the cemetery I began scouring the ground, speed reading old tombstones to find older and older graves. I noted that most of the graves were grouped in plots with Hispanic surnames. Some graves carried elaborate headstones adorned with intricate stone roses. Others were merely marked by hand-tied wooden crosses. One wooden cross was inscribed in felt tip pen, with a farewell from friends offering their love and remembrance. Several mounds had yet to subside, and I carefully avoided them.

And in the very back, near the shade of a dense cedar thicket, lay the Obiedo plots. The man who fed cats beans had been right. And why would I doubt him? It was his wife. I wasn’t sure which grave was hers, or I would have adorned it one day with flowers. But I did notice the Obiedo section had one particularly unusual grave—a white head stone with a frame fashioned to look like petrified logs. It served to remember both the “Padre” and “Madre” of the family and dates for the mother read: Born “1861,” and Died “1802.” But the “8” in the latter was carved over with a “9.” I found the blunder sad at first, then humorous, since I’m sure the deceased would forgive the carver’s error. After all, they are dead.

One month later, a new minister from the east arrived in Boerne, a Baptist evangelist who wanted a short article in the local newspaper I edited, something on his congregation and the good works he planned for the Lord and the community. As we spoke he mentioned long lost relatives in Pipe Creek. I told him he should visit the area, and since he was a Hispanic preacher, I mentioned that he should look in on the solitude at Polly’s Chapel and the cemetery.

Both were unknown to him, but I wondered whether any of his relatives were buried there. “What were your relatives’ names,” I asked.

Both were unknown to him, but I wondered whether any of his relatives were buried there. “What were your relatives’ names,” I asked.

“Obiedo,” he replied. “Obiedo.”

Originally published July 12, 1996 in the Boerne Star